The IJ4EU fund has unveiled an expanded programme of support for watchdog reporting in Europe, with €2 million in grants available to journalists over the next two years to encourage cross-border collaboration on public-interest stories.

Along with money, the Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) fund will assist newsrooms and freelancers across the continent with an enriched menu of training, mentoring, networking opportunities and legal assistance.

The Investigative Journalism for Europe fund is back with a new and improved programme of support for watchdog reporting.

Published on: 09 January 2024

- Open to journalists in more countries than ever

- Grants of up to €50,000 plus training, mentoring and legal help

- New tools to help reporters collaborate across borders

- First call for applications opens on February 1, 2024.

IJ4EU acts as an independent intermediary to channel public and philanthropic money to world-class investigative journalism on transnational subjects without fear of editorial interference.

“Teaming up on big stories across borders requires time and resources that journalists increasingly don’t have,” said Timothy Large, director of independent media programmes at the International Press Institute (IPI), which leads the consortium of non-governmental organisations running the IJ4EU fund.

“IJ4EU’s goal is to stimulate collaborations that would otherwise be impossible. We’ve built a strong reputation within Europe’s investigative journalism community as a trusted provider of independent funds for projects that dare to dig deeper, as well as a defender of our grantees’ right to do their journalism freely.”

Alongside the Vienna-based IPI, the IJ4EU consortium comprises the European Journalism Centre (EJC) in Maastricht and the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF) in Leipzig. In 2024, IJ4EU is proud to welcome the Amsterdam-based Arena for Journalism in Europe (Arena) as a fourth consortium partner.

To date, IJ4EU has disbursed €3.5 million in grants, with core funding from the European Commission and co-financing from philanthropic foundations including Fritt Ord, Open Society Foundations and Isocrates Foundation.

Donors to the IJ4EU fund are not allowed to influence the selection of projects and the IJ4EU consortium and independent juries make all funding decisions.

Every corner of Europe

Since its launch in 2018, IJ4EU has allowed journalists from every corner of Europe to collaborate on topics ranging from organised crime and corruption to migration, security, surveillance, human rights abuses and the environment.

IJ4EU-supported stories have reached hundreds of millions, sparking debate, influencing policy and holding the powerful accountable — from local governments to the loftiest EU institutions.

In 2024 and 2025, IJ4EU will disburse €2 million through two tried-and-tested grant schemes, up from €1.23 million during the previous edition.

IJ4EU’s flagship scheme is the Investigation Support Scheme, offering grants of up to €50,000 to investigative teams of any configuration, including newsrooms, investigative not-for-profits and freelancers.

Managed by IPI, it will allocate €1.5 million to projects.

Running in parallel is the Freelancer Support Scheme, offering grants of up to €20,000 to journalists primarily working outside of newsrooms. The freelancers will also get tailored assistance including mentoring throughout the lifecycle of their projects.

Managed by the EJC, the Freelancer Support Scheme will disburse €500,000.

“The IJ4EU programme enables us to strengthen journalism in two specific areas where EJC knows support is important: collaborative investigative journalism and for freelancers to be able to play a vital role in producing quality and innovative journalism independently,” EJC Director Lars Boering said.

“Combined with networking and learning experiences, we’ve developed ways to make sure the Freelance Support Scheme has a lasting impact.”

Both the Investigation Support Scheme and the Freelancer Support Scheme will have three simultaneous calls for applications during the 2024/25 edition.

The first will open on February 1, 2024, followed by a second in the autumn of 2024 and a third in early 2025. Sign up for the IJ4EU newsletter to keep updated.

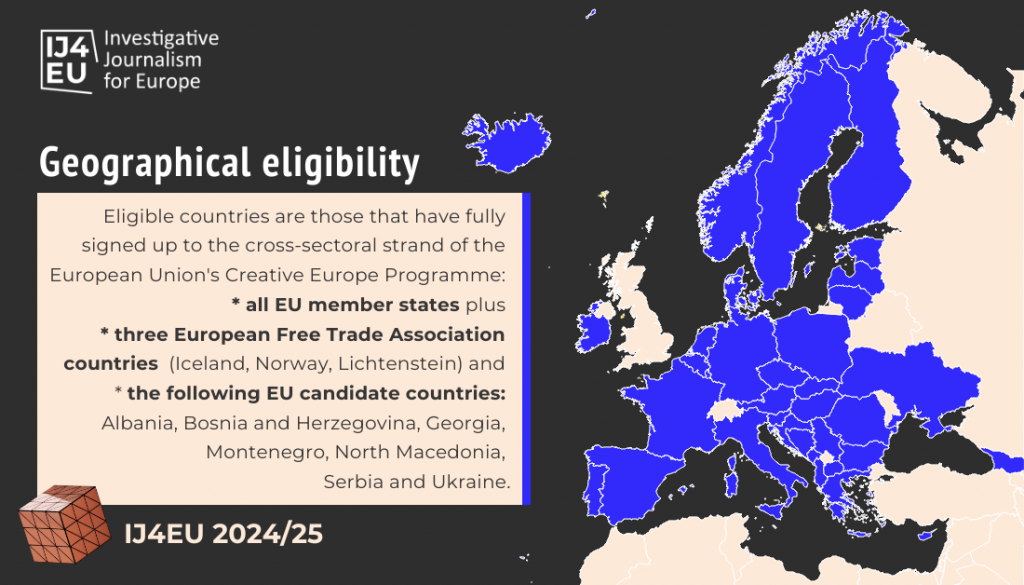

To be eligible for both schemes, teams must have members based in at least two European countries that have fully signed up to the cross-sectoral strand of the European Union’s Creative Europe Programme, which provides core funding for IJ4EU.

That includes all 27 EU member states and the following non-EU countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Norway, Serbia and Ukraine.

As long as teams meet the core eligibility criteria, they may include additional journalists from any country worldwide.

Collaboration across borders

Events familiar from past IJ4EU editions will feature in 2024 and 2025, including an award celebrating excellence in cross-border investigative journalism in Europe and a conference designed to foster networking and innovation.

Managed by ECPMF, both the IJ4EU Impact Award and the Uncovered Conference will take place annually in the autumn. Nominations for the Impact Award open in the spring of 2024.

“Besides honouring the best examples of cross-border journalism in Europe and helping investigative reporters gain the visibility they deserve, the Impact Award is designed to stimulate and enable further transnational collaborations,” Deniz Bozkurt, ECPMF’s IJ4EU programme and event manager, said.

The upcoming IJ4EU programme includes additional networking opportunities, with more money available to bring grantees together for face-to-face encounters, including at Dataharvest – The European Investigative Journalism Conference, organised by Arena in the late spring of 2024 and 2025.

Arena’s inclusion in the IJ4EU consortium also allows extra support for transnational collaboration.

In addition to holding public “Cross-Border Masterclasses” in the run-up to calls for grant applications, Arena will offer moderated “matchmaking” assistance, helping journalists with ideas for collaborative projects to find potential partners.

Meanwhile, IJ4EU grantees can use the Arena Collaborative Desk, a secure digital workspace for remote teams. This access comes with tailor-made tech support and mentoring on editorial coordination, project management and knowledge-sharing.

“We are very happy to contribute with support to journalists, so they can focus on the thing that only they can do: Find and document their story,” Arena Director Brigitte Alfter said.

“We can give tips on how to write a good grant application, we have a network all over Europe, and with the Collaborative Desk, we can help teams to work in a secure digital environment without having to spend a lot of time on it. We look forward to seeing some of the investigations presented at Dataharvest!”

Hostile environments

Along with funding and collaboration support, all IJ4EU grantees will benefit from practical and editorial assistance, allowing them to work independently in a supportive environment.

They will have access to a contingency fund for unexpected legal costs arising from their investigations. They will also receive training in how to mitigate legal dangers, organised by ECPMF.

In the event of threats or intimidation, journalists will have full access to the Media Freedom Rapid Response mechanism managed by ECPMF, as well as advocacy support from IPI, the world’s oldest press freedom organisation.

Grantees will receive resilience training for working in environments hostile to media pluralism, including digital security, safeguarding mental health and coping with smear campaigns and online harassment.