Systemic Racism: Structure, Effects and Dismantling

Discover the origins, components and results of Institutionalized Racism

By Dale B. Taylor, Ph.D.

INTRODUCTION

While growing up in Topeka, Kansas during the time that Brown et al. were mounting a lawsuit against the Board of Education, my family members and I were subjected to constant and relentless acts of racism, both overt and covert, designed to make our lives less productive and less successful than our white neighbors, classmates and coworkers. These acts usually did not consist of name calling, violence, threats of violence or charges of criminality. Those types of individual racist behavior were rarely seen by me personally and when they did occur, I was able to resist the kind of response that would create a lasting record of undesirable or inappropriate behavior on my part which later would have been used to prevent me from reaching bigger more important goals in life.

The continuous racist acts that could not be ignored and for which there was no immediate or direct response were those that were written into laws and official policies and were therefore regularly practiced as accepted procedure throughout all of the city’s daily discourse. To fully understand how these racially biased systems work to generate disparities that result in disadvantaged outcomes for citizens of color, it is necessary to first define the terminology used to refer to racist behavior as well as the structures and regularly practiced procedures that generate racially disparate outcomes. Scientific evidence indicates that in addition to conscious, deliberate cognitive processes, humans also engage in “implicit” or unconscious, effortless, automatic, evaluative processes in which they respond based on images stored in their memory [Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Aversive Racism. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 36. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2004. pp. 1–51]. These memory stores are implanted from very early in life through perceptions of language used by family and through the images and labels assigned to certain groups by educators and by the media [See https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/lethal-effects-media-racial-bias-dale-taylor/].

Racist behavior resulting from “intrinsic” or “implicit” bias consists of individual acts of prejudice that may or may not include violence against a person of a different skin color, ethnic heritage or religious group. However, this type of behavior is not the subject of this paper. To illustrate, in March of 2023, Oklahoma’s McCurtain County Sheriff Kevin Clardy was recorded talking to City Commissioner Mark Jennings about killing reporters and hanging black people. While this racially biased exchange revealed intense feelings of internalized racism harbored by these public officials, it was not itself “systemic.”

Systemic Racism

Racism is not a personal choice, it is by design. Systemic racism, also referred to by terms such as “institutional racism,” “systemic bias” or “structural racism,” consists of laws, written and unwritten rules, operational procedures, policies, practices, traditions and structural deficits in opportunity that are purposely designed to result in inequitable treatment leading to negative outcomes for a specific group of people, such as native, Hispanic or black Americans. For example, when the Topeka Board of Education established a rule prohibiting African-American children from attending the same elementary schools or using the same textbooks as white children, they also spent school board funds to establish four schools exclusively for black children and to bus me out of my all black neighborhood up eleventh street right past all-white Lowman Hill Elementary School to a different all-black neighborhood where Buchanan Elementary School was located. We later would learn that segregated schools had very different levels of funding for staff and upkeep, different student-teacher ratios, different facilities such as no library, assembly hall, cafeteria or gymnasium at Buchanan, and different textbooks often with two versions of the same title published under the same Library of Congress number. Similar practices were occurring in other parts of the city in order to purposely provide a lower quality education to children of color. There was no recourse for any of our parents who might have preferred for us to attend our nearest neighborhood school. It was their reaction to this oppressive system of discrimination that prompted a group of parents to seek the services of NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall to pursue the Brown vs. Board of Education lawsuit that was appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court where it resulted in the unanimous 1954 school desegregation decision.

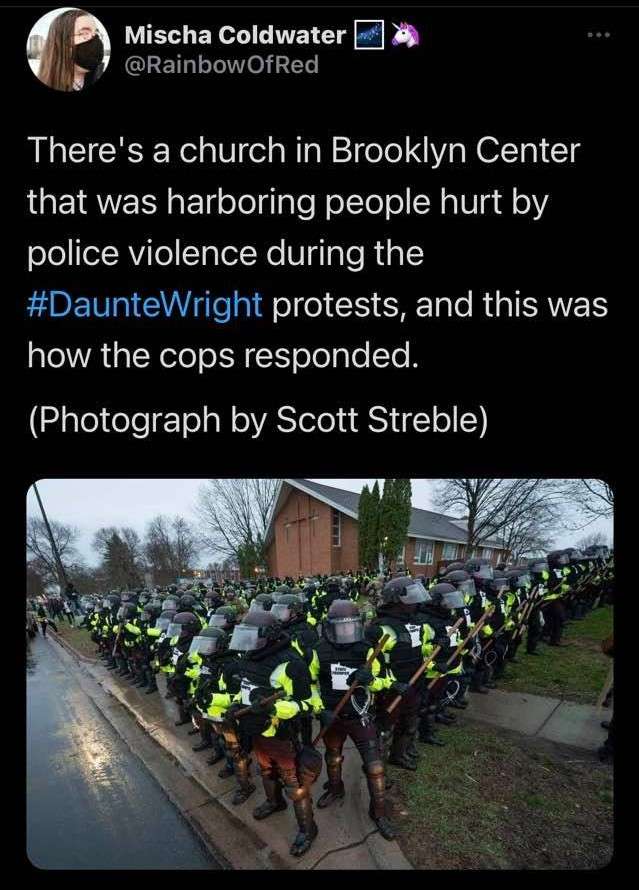

A much more current example of systemic racism occurred in 2024 when the Wisconsin Governor stated that a group of legislators are refusing to release funding for public schools that include DEI or Diversity-Equity-Inclusion programming. This is a perfect example of “systemic racism” perpetuated by lawmakers who use their positions to keep people of color from succeeding in gaining the education that could help overcome the structured poverty and deprivation that leads to devastating racial disparities. They know that Wisconsin consistently ranks as the #1 Worst State for Black Americans because the intentionally segregated housing patterns that most black students come from have relegated them to substandard poorly funded prep schools due to purposely lowered appraised property valuations that are used as the basis for school funding in neighborhoods where a child’s address determines which school they attend. Lawmakers then strive to prevent all forms of help such as may be provided by DEI programs at secondary or collegiate levels that could help overcome the resulting gaps in student preparation. These same legislators also know that surveillance policing with stop-&-frisk tactics in those areas (as opposed to on-call policing) has tagged large numbers of potential college students with life-changing misdemeanor or criminal charges, unaffordable fines and fees, prison time or arrest records which—regardless of proven innocence or dropped charges—further limits college eligibility, job qualifications and housing prospects among this population. Even one misdemeanor charge often prevents housing eligibility, vehicle ownership, educational opportunity and most employment.

Legislators especially strive to prevent financial assistance to those students of color who do qualify for college because they know that college funding via household wealth in segregated areas is severely limited since home equity loans, which are often used to pay for college, are not available to families who live in rented homes, publicly funded housing, homes with low property valuations, people already paying high monthly mortgage installments, families with under-educated heads of household, families supported by any form of public assistance, homes with low or no accrued equity, or to any loan applicant with an arrest record or who is denied at the banker’s own discretion. The resulting poverty results in homelessness and food insecurity, and generates dependence on numerous other sparsely rationed resources such as poorly funded infrastructure, absent or poorly maintained recreational facilities, distant emergency services, sparse public transportation, few job opportunities, no artistic outlets, too few voting sites, poor quality nutrition, nonexistent or discriminatory financial services and difficult health care access with biased health care providers. This systematic oppressive deprivation is normalized in the public eye via media conditioning that implants racial bias through use of demonized descriptors and criminalized images designed to negatively stereotype citizens of color living in segregated areas. At the same time, they ignore stories about positive accomplishments by black and brown people. To illustrate, the Baltimore Sun published a 2022 apology to its Black constituents stating in part that:

“The Baltimore Sun promoted policies that oppressed Black Marylanders; we are working to make amends. The Baltimore Sun frequently employed prejudice as a tool of the times. It fed the fear and anxiety of white readers with stereotypes and caricatures that reinforced their erroneous beliefs about Black Americans. And this newspaper reinforced policies and practices that treated African Americans as lesser than their white counterparts — restricting their prospects, silencing their voices, ignoring their stories and erasing their humanity. The Sun sharpened, preserved and furthered the structural racism that still subjugates Black Marylanders in our communities today.”

The Sun also admitted to “editorials seeking to disenfranchise Black voters, failure to hire any African American journalists, identification of Black people by race in articles, reliance for too long on the word of law enforcement over that of Black residents, an absence of stories about issues relevant and important to non-white communities, and a failure to feature Black residents in stories of achievement and inspiration rather than crime and poverty.”

Although most systemic racism is based on statutory or other written rules, it is not uncommon for some of its components to allow discretionary applications, such as when a law is written to appear as though it applies to everyone but the clear intent is to only enforce it when the accused person is black. A prominent example was exposed in 2021 when Governor Ralph Northam of Virginia delivered a public apology to the African-American community after the death penalty was repealed in that state. According to Northam’s office, there were 45 executions for rape in Virginia during the 44 years from 1908 to 1951 and ALL of those killed were black. He granted posthumous pardons for a group of seven black men between the ages of 18 and 23 who were executed in 1951 for allegedly raping a white woman in Martinsville, VA. Some of them could not read the confessions they signed and none had an attorney present during questioning. In his statement, Northam said “The Commonwealth of Virginia played an irrefutable role in the political, economic, and social disenfranchisement of Black Americans, and helped shape, actively enforce, and uphold the racially discriminatory Jim Crow laws which were formed to further systematically oppress Black Americans and maintain the status quo.” The pardon also said that race “played an undeniable role during the identification, investigation, conviction, and the sentencing.” Recognizing the racial disparity, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1977 that the death penalty was cruel and unusual punishment for rape. These examples describe “systemic” racism because the legal system was used as an unassailable tool of oppression requiring U.S. Supreme Court action to dismantle.

The foundation of systemic racism, however, cannot be understood only through studying written laws or exposing biased enforcement of statutes. Systemic racism has numerous components each of which is interdependent with the others. Throughout this paper, we will examine the system as a whole while describing its four major components—housing, education, policing, health care—as we seek to determine what effects each component has on the creation and sustaining of systems that perpetuate racial disparities. This level of discernment is necessary in order to begin to determine effective mechanisms for dismantling this country’s pervasive system of racial oppression. “Racial and ethnic inequalities loom large in American society,” according to the Urban Institute, a Washington, D.C. think tank founded by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968. “People of color face structural barriers when it comes to securing quality housing, health care, employment, and education. Racial disparities also permeate the criminal justice system.” Systemic racism can be dismantled only when each of us understands the scaffolding holding it in place.

1: Residential Segregation: The Cornerstone of Systemic Racism

The physical separation of black Americans from white residents and their confinement within the boundaries of segregated living spaces is the essential Foundational Component of Systemic Racism. All other aspects are results of this housing separation, they exist to sustain residential limitations, or they depend on residential restrictions in order to be effective in causing disadvantages for people of color. By limiting areas in which blacks can live, power brokers can use political, financial, judicial and regulatory systems to control people’s behavior, personal freedom, opportunity, living conditions and the presence or absence of resources—both good and bad—that are present in those neighborhoods.

In large U.S. cities, resources that are controlled in racially segregated residential areas include food which is controlled by manipulating prices, quality and grocery license availability in ways that have unique effects on those living in geographically isolated black housing areas. Prices and access to essential services such as water, natural gas and electricity also are managed from outside of these areas. Job opportunities often become scarce when a neighborhood becomes primarily black occupied and overcrowded. The resulting income deprivation then causes some to resort to prostitution or other illegal means to survive financially. Their plight facilitates the influx of unsavory and dangerous commodities being funneled in from outside such as illegal drugs, alcohol, guns and pornography, none of which are originally manufactured within the area by its black residents. Government authorities then respond by replacing ‘on-call’ policing with ever-present ‘surveillance’ policing using stop-and-frisk tactics which leads to more arrests, convictions, mass incarcerations and executions.

Public funding becomes minimal or frequently denied for segregated area infrastructure such as street repair, street construction, street lighting, public transportation and schools. Access to or denial of emergency services, health care and recreational facilities in a segregated area also are controlled by outsiders through manipulation of licenses, zoning, building permits and other regulatory instruments. Residents of these areas still are subjected to increased taxation, constant police surveillance, decreased voting access and increased susceptibility to “eminent domain” or “urban renewal” property seizures for highways, airports, military installations and shopping malls. Housing segregation, therefore, makes it possible for these and other intentional barriers to be used to make life difficult for black and any other specified isolated population group. This is why Residential Segregation must be understood as the most basic and important of all oppressive systems to be addressed and discontinued before lasting change can be achieved. Its effects are far-reaching and cannot be overcome by hard work, political participation, education or any other independent effort put forth by area residents. As this paper will demonstrate, Open Housing is the only effective sustainable remedy.

HOUSING DISCRIMINATION

The availability of housing is the first question to be addressed when an individual or family seeks to reside in a certain region or city. However, those in power who may want to deny freedom and opportunity for people of color (POC) know that there are many factors which can be used to limit their ability to occupy a specific house in a desired neighborhood regardless of whether the potential occupant has the money, the income or the appropriate credit history. They also know that home ownership is the most necessary factor for a family to build household and generational wealth in the U.S. economy. This paper will reveal some of the most important devices used to prevent a black citizen from obtaining a home in a desirable neighborhood and forcing that family to reside in substandard housing in a segregated area with little to no chance of ever using that home as a basis for building wealth.

Because segregated housing is essential for Systemic Racism to exist without apartheid laws, there are numerous financial, regulatory and discretionary mechanisms used to prevent black residents from buying, selling, renting, building, occupying or accruing equity in a house outside of a designated geographical area. This paper will illuminate many of the time-tested tactics systematically utilized through a partnership between government, real estate and banking sectors designed to restrict urban land use to either black or white residents with preferred areas reserved for whites.

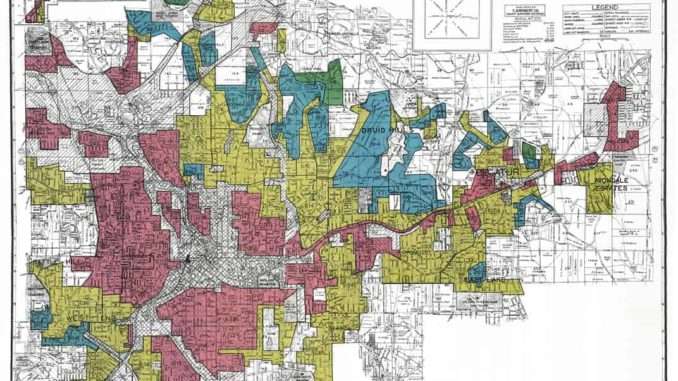

REDLINING: Its Origin, Structure & Remedies

Housing discrimination has been a major obstacle faced by African-Americans since emancipation. Racially separated housing became official government policy with implementation of the system known as “redlining.” The U.S. Department of Justice defines “Redlining” as an illegal practice in which lenders avoid providing services to individuals living in communities of color because of the race or national origin of the people who live in those communities. It first became official policy in 1933 when the federal government sought to establish an economic foundation for racial discrimination. In that year, a federal agency called the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) was founded under newly elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “New Deal.” The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was then established by the National Housing Act of 1934 to regulate interest rates and mortgage terms after the banking crisis of the late 1920s and early 1930s. Through the newly created FHA, the federal government began to insure mortgages issued by qualified lenders, thereby providing mortgage lenders protection from default. If a borrower failed to make their payments, the FHA was required to cover the unpaid balance. It implemented segregated housing policies by using color coded maps developed by the HOLC and referred to as “residential security maps” to tell banks which loans would be insured by the federal government. Loan insurability was not based on the quality of the housing or the ability of borrowers to repay. It was exclusively based on the share of Black people in the neighborhood: Green – most desirable; Blue – still desirable; Yellow – declining; Red – any area Black Americans lived in or even lived nearby meant “too hazardous to lend to.” This practice called “Redlining” was created by the federal government, administered by the HOLC, and adopted by lenders in 239 U.S. cities that were mapped in the four colors. In the Underwriting Handbook used by the FHA, African-American neighborhoods were marked as ‘ineligible’ for FHA loans. Resident “Negroes” in any area were referred to in government documents as “subversive elements.” The stated purpose of the HOLC loan program was to help veterans but not all veterans could benefit. Between 1933 and 1952, 98% of the home loans went to white Americans, thus excluding nearly all black Americans from this federal program.

Housing discrimination has been a major obstacle faced by African-Americans since emancipation. Racially separated housing became official government policy with implementation of the system known as “redlining.” The U.S. Department of Justice defines “Redlining” as an illegal practice in which lenders avoid providing services to individuals living in communities of color because of the race or national origin of the people who live in those communities. It first became official policy in 1933 when the federal government sought to establish an economic foundation for racial discrimination. In that year, a federal agency called the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) was founded under newly elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “New Deal.” The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was then established by the National Housing Act of 1934 to regulate interest rates and mortgage terms after the banking crisis of the late 1920s and early 1930s. Through the newly created FHA, the federal government began to insure mortgages issued by qualified lenders, thereby providing mortgage lenders protection from default. If a borrower failed to make their payments, the FHA was required to cover the unpaid balance. It implemented segregated housing policies by using color coded maps developed by the HOLC and referred to as “residential security maps” to tell banks which loans would be insured by the federal government. Loan insurability was not based on the quality of the housing or the ability of borrowers to repay. It was exclusively based on the share of Black people in the neighborhood: Green – most desirable; Blue – still desirable; Yellow – declining; Red – any area Black Americans lived in or even lived nearby meant “too hazardous to lend to.” This practice called “Redlining” was created by the federal government, administered by the HOLC, and adopted by lenders in 239 U.S. cities that were mapped in the four colors. In the Underwriting Handbook used by the FHA, African-American neighborhoods were marked as ‘ineligible’ for FHA loans. Resident “Negroes” in any area were referred to in government documents as “subversive elements.” The stated purpose of the HOLC loan program was to help veterans but not all veterans could benefit. Between 1933 and 1952, 98% of the home loans went to white Americans, thus excluding nearly all black Americans from this federal program.

Real Estate and Lender Complicity

Once geographical limitations were designated by the government identifying where African-Americans lived, the homes in that area became the only ones shown to black home seekers by real estate agents. These areas were identified to banks and real estate brokers as “high risk” areas characterized by housing and lending discrimination that prevented homeowners from obtaining insured mortgages to purchase, replace or improve existing homes. In most cities, these areas contained substandard housing, multiunit rentals owned by absentee landlords, or were near factories or railroads that produced air, water and noise pollution. Residents were the first to be uprooted when such areas were subjected to “urban renewal” under which all land ownership reverted to the government so that a large scale project such as a freeway could be built right through the heart of the neighborhood. Having been created by the government and implemented then and now by private lenders, today’s DOJ acknowledges that the system has had a lasting negative effect.

Redlining was outlawed by the by the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and further prohibited by the 1974 Equal Credit Opportunity Act, but the damage had been done and the practice has continued especially in major U.S. cities. The reason is that although official federal policy changed in 1968, those changes included no remedies for past injustices or any penalties for continuing to propagate financial policies practiced throughout decades of past redlining discrimination in housing patterns. Consequently, the courts continued to uphold residential separation in cases that challenged the status quo since there was no legal mandate to change what had already been established. Also, there was no campaign to re-educate bank lenders regarding the revised FHA mortgage insurance requirements that now permitted insuring home loans in areas where blacks reside. Consequently, the white public continues to believe erroneously that if black residents move into their neighborhood, their own property will be devalued and their ability to secure federally insured loans will be diminished. These beliefs are further reinforced by home appraisers who place below-market values on homes owned by or located near black residents and by realtors who steer black home buyers away from white occupied neighborhoods by only showing them homes in areas where black residents already comprise the majority.

Another post-1968 result of court decisions upholding practices and conditions resulting from redlining was that local and especially private regulations that discriminated against black home buyers were allowed to continue and even to expand. In recent years, however, the FHA and its affiliates have begun an active program of enforcement that has resulted in numerous very costly fines being paid as part of settlements of cases brought by federal regulatory agencies against major banks in numerous states. In a 2021 case, the Justice Department, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Tennessee, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) announced an agreement to resolve allegations that Trustmark National Bank engaged in lending discrimination by redlining predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in Memphis, Tennessee. The parties’ proposed consent order was filed in conjunction with a complaint in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Tennessee. The complaint alleges that Trustmark National Bank violated the Fair Housing Act and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which prohibit financial institutions from discriminating on the basis of race, color or national origin in their mortgage lending services.

The complaint also alleges that Trustmark National Bank violated the Consumer Financial Protection Act, which prohibits offering or providing to a consumer any financial product or service not in conformity with federal consumer financial law. Specifically, the complaint alleges that, from 2014 to 2018, Trustmark engaged in unlawful redlining in Memphis by avoiding predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods because of the race, color, and national origin of the people living in, or seeking credit for properties in, those neighborhoods. The complaint further alleges that Trustmark’s branches were concentrated in majority white neighborhoods, that the bank’s loan officers did not serve the credit needs of majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, that Trustmark’s outreach and marketing avoided those neighborhoods, and that Trustmark’s internal fair-lending policies and procedures were inadequate to ensure that the bank provided equal access to credit to communities of color. The justice department had opened its investigation after one of Trustmark’s regulators, the OCC, referred the matter. “Trustmark purposely excluded and discriminated against Black and Hispanic communities,” said Director Rohit Chopra of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). “The federal government will be working to rid the market of racist business practices, including those caused by discriminatory algorithms.”

Under the 2021 agreement, Trustmark will invest $3.85 million in a loan subsidy fund to increase credit opportunities for current and future residents of predominantly Black and Hispanic areas in Memphis; dedicate at least four mortgage loan officers or community lending specialists to these neighborhoods; and open a loan production office in a majority Black and Hispanic neighborhood in Memphis. Trustmark will devote $400,000 to developing community partnerships to provide services to residents of majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in Memphis so as to increase access to residential mortgage credit. Trustmark will devote at least $200,000 per year to advertising, outreach, consumer financial education and credit repair initiatives in and around Memphis. Trustmark also will have to pay a total civil money penalty of $5 million to the OCC and CFPB. Trustmark already has established a Fair Lending Oversight Committee and designated a Community Lending Manager who will oversee these efforts and work in close consultation with the bank’s leadership. “Home ownership is the foundation of economic success for most American families,” said Acting U.S. Attorney Joseph C. Murphy Jr. for the Western District of Tennessee. “Fair lending practices required by federal law — and the enforcement of those laws — ensure a better future for all Americans. Our office believes that enforcement actions of this type are essential to a fair lending system that benefits everyone, and we will continue to prioritize these cases.”

In August 2021, the Justice Department and the OCC announced a similar redlining settlement with Cadence Bank, headquartered in Atlanta with offices in Houston. Under the settlement, Cadence will invest over $5.5 million to increase credit opportunities for residents of majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in Houston. The DOJ alleged that Cadence Bank violated the Fair Housing Act and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which prohibit financial institutions from discriminating on the basis of race, color or national origin in their mortgage lending services. Specifically, the complaint alleged that, from 2013 to 2017, Cadence engaged in unlawful redlining in the Houston area by avoiding predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. The department also alleged that Cadence’s branches were concentrated in majority white neighborhoods, that the bank’s loan officers did not serve the credit needs of majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods and that the bank’s outreach and marketing avoided those neighborhoods.

Under the department’s settlement, which was approved by the District Court on August 31, 2021, Cadence will invest $4.17 million in a loan subsidy fund for residents of predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in the Houston area, $750,000 for development of community partnerships to provide services that increase access to residential mortgage credit in those neighborhoods, and at least $625,000 for advertising, outreach, consumer financial education, and credit repair initiatives. The bank will dedicate at least four mortgage loan officers to majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in Houston and open a new branch in one of those neighborhoods. Cadence will employ a director of community lending and development who will oversee these efforts and work in close consultation with the bank’s leadership. The bank will take these steps in addition to other fair lending measures it has already put in place.

“When banks fail to provide equal access to credit in communities of color, they violate our civil rights laws and they deprive people in those communities of the opportunity to build wealth,” said Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. “Redlining is an illegal practice that has far-reaching consequences for people of color, their families and for the neighborhoods where they live. The Civil Rights Division will continue to enforce our nation’s fair lending laws to ensure that qualified applicants and borrowers can access credit and invest in their financial futures without facing unlawful barriers.” “There is no place for discrimination in the federal banking system,” said Acting Comptroller of the Currency Michael J. Hsu. “The OCC will use the full force of our authority to correct fair lending violations with our supervisory and enforcement tools, including civil money penalties, cease and desist orders, and requiring restitution for customers harmed as a result of any discriminatory practices.”

“The Fair Housing Act and Equal Credit Opportunity Act are intended to provide equal treatment for all people in their pursuit of home ownership and financing,” said Acting U.S. Attorney Kurt R. Erskine for the Northern District of Georgia. “This case highlights the need for vigilance in addressing practices which treat certain communities unfairly and has led to an agreement with Cadence Bank intended to improve the fairness of its business practices and to make remedial financial investments in the negatively impacted communities. This office will continue in its efforts to eliminate housing and credit discrimination.”

The department’s Civil Rights Division and the OCC have long been engaged in work that seeks to make mortgage credit and homeownership accessible to all Americans on the same terms, regardless of race or national origin, and regardless of the neighborhood in which they live. In January 2021, President Biden reaffirmed the critical role of the federal government in addressing legacies of housing segregation and discrimination, declaring that it is the policy of his Administration to eliminate “racial bias and other forms of discrimination in all stages of home-buying and renting.” (See Memorandum on Redressing Our Nation’s and the Federal Government’s History of Discriminatory Housing Practices and Policies, The White House, Jan. 26, 2021).

Home Loan Denials.

Home loans are used to purchase or improve a home and to acquire capital for other purposes by refinancing a home. Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke for the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division said “Enforcement of our fair lending laws is critical to ensure that banks and lenders are providing communities of color equal access to lending opportunities. Equal and fair access to mortgage lending opportunities is the cornerstone on which families and communities can build wealth in our country.” However, many lending institutions have engaged in racially discriminatory patterns of loan denials regardless of borrower credit ratings or repayment capabilities. These practices recently have drawn legal attention from federal agencies. For example, on December 17, 2021, Old National Bank, the largest financial services holding company in Indiana, reached out to the Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana (FHCCI) offering $30 million to settle a federal ‘redlining’ complaint in order to avoid a court proceeding. The bank has agreed to lend more than $27 million to qualified Black applicants. It will also contribute more than $3 million to create programs to help Black home seekers secure mortgages and to invest in majority Black neighborhoods throughout the Indianapolis-Carmel-Anderson metropolitan area. Between 2019 and 2020, Old National Bank approved more than 2,200 mortgage loans in the Indianapolis-Carmel-Anderson metropolitan area, but only 37 Black applicants, less than 1.7% of the total, were approved for mortgage loans. Following the complaint, Old National Bank contacted FHCCI to reach an agreement that would repair past discriminatory practices. The agreement will remain in effect for three years, even though Old National does not admit to any wrongdoing in the settlement. In a press release, FHCCI executive director Amy Nelson said “The FHCCI and (Old National Bank) have created a guide for other financial institutions to address their own disparities and ensure fair lending opportunities for all.” Continued nationwide enforcement action of this type is essential to achieving progress in removing the cornerstone of systemic racism in this country.

High Interest Loans

Recent studies cited by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition have found that when conventional loans were made in HOLC red-coded “Hazardous” areas, they had higher interest rates for borrowers. They also found discriminatory practices by the HOLC in allowing brokers to follow local housing segregation standards in the resale of properties acquired by foreclosure. A 2014 study extended beyond the HOLC maps themselves to encompass later FHA mortgage risk maps of Chicago and found that those maps directly impacted lending decisions, barring loans over large sectors of the city.

According to USA Today, the home ownership gap between white and black Americans is wider than it was in 1960 and the home ownership rate for black Americans is expected to drop from 41% in 2020 to 40% in 2040. Part of the reason is the wide variety of loan industry mechanisms used to impair or prevent black home ownership. Loan officers can decide to offer only loans that carry higher interest rates making the loan payments higher and the payoff periods much longer. Both of these factors make it very difficult to build home equity against which to borrow for other purposes such as higher education or to start a business. Also, loan qualification standards often are much higher and may be unreachable for black borrowers forcing them to retreat to lower quality homes in areas with lower land valuations. Use of such tactics largely explains why today’s black college graduates live in communities where property valuations are lower than those occupied by whites without a degree.

Interest-Only Loans

Loan contracts that allow borrowers to pay monthly payments that apply only toward the interest owed on the loan are often offered to and accepted by black borrowers since they do allow people to purchase and live in a house or condominium without renting or signing a lease agreement. However, this type of financing also does not allow the occupant to ever actually own that dwelling. While payments may be lower and loan qualifications easier to meet, the borrower suffers the disadvantage of never building equity against which to borrow for other purposes such as a car purchase, medical bill or major vacation. Although this method of borrowing may allow a black home buyer to technically own a home, the occupant cannot hope to profit from eventual sale of the home and the lender always holds a 100% lien on that dwelling with the ability to foreclose or otherwise reclaim or dispose of the property with little to no recourse available to the resident.

Land Contracts

The use of Land Contracts became widespread during the “great migration” of the 20s, 30s and 40s during which black families moved north to major cities in search of work and life away from the constant racist pressures of the Jim Crow south. Their search for housing was met with a wide variety of problems such as racially biased sellers and multiple obstacles to home financing. When government color coding of neighborhoods became known, white property owners became aware that the presence of even one Black resident in their area meant that properties in that part of town would be purposely devalued and financing would become much more difficult or impossible to obtain using one’s home as collateral. In many U.S. cities, white families fled racially changing neighborhoods and the same financial institutions that denied loans to creditworthy black buyers were happy to give mortgages to white speculators who bought the newly available homes at huge discounts only to sell them months later to Black families for double or quadruple what they paid, says Beryl Satter, professor of history at Rutgers University and the author of “Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America.” This practice required lenders to work in close partnership with other sectors of the housing industry such as real estate agents and home appraisers.

In Chicago during the 1950s and ‘60s, many working-class black families were forced to turn to speculative sellers when they found that banks would not loan them money to buy homes since the federal government refused to insure mortgages in redlined neighborhoods. These speculators offered contractual instruments such as land contracts that many banks did not offer. Land contract buyers were required to pay a down payment, high monthly payments and maintenance of the house while the deed remained in the seller’s name until the very last payment was made. A single missed payment was grounds for eviction. Facing income disparities and interruptions such as economic recessions, strikes, layoffs or events requiring unpaid leave from a job, many Black borrowers lost their homes to land contractors along with any equity that had accrued.

The “Great Migration”

The Great Migration was the relocation of more than 6 million Black Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North, Midwest and West from about 1916 to 1970. It was driven by unbearable conditions existing after the Civil War and the Reconstruction era during which racial inequality persisted across the South and the segregationist policies known as “Jim Crow” became law. And while the Ku Klux Klan had been officially dissolved in 1869, the KKK continued underground after that, and intimidation, violence and lynching of Black southerners were common practices in the Jim Crow South. Blacks were forced to make their living working the land due to Black codes and the sharecropping system, which offered little in the way of economic opportunity especially after crops were damaged by a regional boll weevil infestation in the 1890s and early 1900s. Beginning in about 1910, Black people left the South, usually traveling by train, boat or bus while a smaller number had automobiles or horse-drawn carts.

When World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, urban areas in the North, Midwest and West faced a shortage of industrial laborers as the war put an end to the steady tide of European immigration to the United States. With war production kicking into high gear, recruiters enticed Black Americans to come north to the dismay of white Southerners. Black Americans headed north to take advantage of the need for industrial workers. Many new arrivals found jobs in factories, slaughterhouses and foundries, where working conditions were arduous and sometimes dangerous. Female migrants had a harder time finding work, spurring heated competition for domestic labor positions. Aside from competition for employment, there was also competition for living space in increasingly crowded cities. While segregation was not legalized in the North, racism and prejudice were nonetheless widespread. After the U.S. Supreme Court declared racially based housing ordinances unconstitutional in 1917, some residential neighborhoods enacted covenants requiring white property owners to agree to not sell to Black people. These would remain legal until the Court struck them down in 1948. During the Great Migration, Black people began to build a new place for themselves in public life, actively confronting racial prejudice as well as economic, political and social challenges to create a Black urban culture that would exert enormous influence in the decades to come.

Public Housing aka “The Projects”

Following emancipation in the 1860s, blacks were free to move around and many migrated to major cities to secure stable employment. As overcrowding became the norm in slum-laden municipalities, government officials acknowledged that there was insufficient living space in areas designated for Black and other working-class people. Model tenements were built as early as the 1870s which attempted to use new architectural and management models to address the physical and social problems of the slums. These attempts were limited by available resources, and early efforts were soon redirected towards building code reform.

In 1923, the City of Milwaukee, under Mayor Daniel Hoan, having experienced rapid growth in its manufacturing sector, implemented the country’s first public housing project, known as Garden Homes. This experiment with a municipally-sponsored housing cooperative saw initial success, but was plagued by development and land acquisition problems. Eventually, the board overseeing the project dissolved the Garden Homes Corporation just two years after construction on the homes was completed. The city also had to deal with a World War I-era moratorium on new housing construction.

Rather than offering publicly funded housing loans to migrating Black workers to build or buy homes in urban or suburban residential spaces, public officials decided to create additional living space in previously established limited areas by building publicly funded high-rise apartment buildings to be rented out to working occupants. These residences resulted in hundreds of thousands of people per square mile living in very close proximity to each other and under close surveillance by police and in-house security forces. Subsidized apartment buildings, often referred to as housing projects or simply “The Projects,” have a complicated and often notorious history in the United States. While the first decades of projects were built with higher construction standards and a broader range of incomes among some applicants, over time, public housing increasingly became the housing of last resort in many cities. Several reasons have been cited for this negative trend including the failure of Congress to provide sufficient funding, a lowering of standards for occupancy, and mismanagement at the local level. Furthermore, housing projects have also been seen to greatly increase concentrated poverty in a community, leading to several negative external problems. Crime, drug and alcohol usage, and educational under-performance are all widely associated with housing projects, particularly in urban areas. As a result of their various problems and diminished political support, many of the traditional low-income public housing properties constructed in the earlier years of the program have since been demolished.

Subsidized Housing

In the spring of 1934, federal Public Works Administration (PWA) administrator Harold Ickes directed the Housing Division to undertake the direct construction of public housing, a decisive step that would serve as a precedent for future housing legislation and the permanent public housing program in the United States. Between 1934 and 1937, the Housing Division constructed fifty-two housing projects across the United States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Atlanta’s Techwood Homes opened on September 1 of 1936 and was the first of the fifty-two to open. Based on the residential planning concepts of Clarence Stein and Henry Wright, these fifty-two projects are architecturally cohesive, composed of one to four story row houses and apartment buildings and arranged around open spaces, creating traffic-free play spaces intended to define community lift. Many of these projects were built on slum land, but land acquisition proved difficult making it necessary to also purchase abandoned industrial sites and vacant land. Two early projects were constructed on an abandoned horse racing track. At Ickes’ direction, many of these projects were purposely segregated, designed and built for either whites or African-Americans. Race was largely determined by the neighborhood surrounding the site, as American residential patterns, in both the North and South, were highly segregated in accordance with the federal color coded mapping system described above.

In 1937, the Wagner-Steagall Housing Act of 1937 replaced the temporary PWA Housing Division with a permanent quasi-autonomous agency to administer housing. This new United States Housing Authority operated with a strong bent towards supporting local efforts in locating and constructing housing and placed caps on how much could be spent per housing unit. The cap of $5,000 was a hotly contested feature of the bill as it would be a considerable reduction of the money spent on PWA housing and was far less than advocates of the bill had lobbied to get.

Building on the former Housing Division’s organizational and architectural precedent, the USHA built housing in the build-up to World War II, supported war-production efforts and battled the housing shortage that occurred after the end of the war. In the 1960s, across the nation, housing authorities became key partners in urban renewal efforts, constructing new homes for those displaced by highway, hospital and other public efforts.

Beginning primarily in the 1970s the federal government turned to other approaches including the Project-Based Section 8 program, Section 8 certificates, and the Housing Choice Voucher Program. In the 1990s the federal government accelerated the transformation of traditional public housing through HUD’s HOPE VI Program. Hope VI funds are used to tear down distressed public housing projects and replace them with mixed communities constructed in cooperation with private partners. In 2012, Congress and HUD initiated a new program called the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program.[8] Under the demonstration program, eligible public housing properties are redeveloped in conjunction with private developers and investors.

In the United States, subsidized housing is administered by federal, state and local agencies to provide subsidized rental assistance for low-income households. Public housing is priced much below the market rate, allowing people to live in more convenient locations rather than move away from the city in search of lower rents. In most federally-funded rental assistance programs, the tenants’ monthly rent is set at 30% of their household income.[2] Now increasingly provided in a variety of settings and formats, originally public housing in the U.S. consisted primarily of one or more concentrated blocks of low-rise and/or high-rise apartment buildings. These complexes are operated by state and local housing authorities who are authorized and funded by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In 2020, there were 1 million public housing units.[3]

Biased Housing Appraisals

In order to sustain segregated housing as the cornerstone of institutional racism, real estate agents do their part by showing to black buyers only those homes for sale in neighborhoods designated as available for black residents. Black home sellers in these areas are targeted by appraisers who do their part to prevent them from benefitting from the value of their homes by assuring that homes are greatly undervalued so that their owners are unable to profit from home sales and cannot build equity as a basis for borrowing money. It then becomes difficult to use the home as an investment, to borrow to make home improvements or other purchases, or to sell a red-lined area home at an appreciated value. Also, potential buyers often cannot acquire loans due to difficult loan acquisition requirements.

As revealed in the three examples below, appraisers often set home valuations so low that sellers are faced with losing tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars needed to pay outstanding costs, finance their next home, or start to build household wealth. For example, a black homeowner, Carlette Duffy, in Indianapolis launched a legal fight after her house was twice valued at about half of what she had anticipated. She filed a housing discrimination complaint alleging that the low appraisals were offered because of her race. She had attempted to take advantage of lower interest rates in 2020 by refinancing the mortgage loan for her home in a neighborhood near downtown Indianapolis. The first valuation came back at $125,000, while a second, conducted by a different mortgage broker and appraiser, said it was worth only $110,000. When applying for a third valuation, she did not declare her race on the application, she removed family photographs and African American artwork, and she got the white husband of a friend to stand in for her during the appraisal visit. The house was then valued at $259,000, over twice the highest previous appraisal. Apply this same type of differential valuation to other components of our racialized economic system such as jobs, salaries, business financing and educational opportunity over multiple generations, and you might just begin to grasp the vast systemic problems that generate the many disparities plaguing Black American families every day.

A second case demonstrates how racially oppressive financing policies target Black homeowners even when a property is not located in a redlined area. Nathan Connolly and Shani Mott in 2021 welcomed an appraiser into their house in an upscale area of Baltimore, hoping to take advantage of historically low interest rates and refinance their mortgage. They believed that their house — improved with a new $5,000 tankless water heater and $35,000 in other renovations — was worth much more than the $450,000 that they paid for it in 2017. Home prices had been on the rise nationwide since the pandemic. In Baltimore, they had gone up 42% in the past five years, according to Zillow.com. However, a Maryland appraisal company, 20/20 Valuations, put the home’s value at $472,000, and in turn, a mortgage lender, LoanDepot, totally denied the couple a refinance loan. Connolly said he knew why: He, his wife and three children, ages 15, 12 and 9, are Black. Connolly, a professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, is an expert on redlining and the legacy of white supremacy in American cities and much of his research focuses on the role of race in the housing market. Some months after that first appraisal, the couple applied for another refinance loan, removed family photos and had a white male colleague — another Johns Hopkins professor — stand in for them. The second appraiser valued the house at $750,000.

In California, homeowners are looking to cash in on greater home value as the cost of homes is on the rise. San Francisco Bay Area Black homeowners Paul and Tenisha Tate-Austin have filed a fair housing lawsuit in a federal district court against Janette Miller and her appraisal firm Miller and Perotti Real Estate Appraisers Inc., whose valuation of their home was almost $500,000 less than its true value. Attorneys for the couple argue in the lawsuit that “Marin City has a long history of undervaluation based on stereotypes, redlining, discriminatory appraisal standards, and actual or perceived racial demographics.” In 2016 the couple purchased their home for $550,000 and, over the next few years, invested $400,000 in renovations that included an in-law unit and an outdoor deck. Four years later, the couple hired an appraiser in order to learn the new value of their home. The appraiser, whom the couple described to local station ABC7 as an older white woman, was impressed with the addition of windows that overlooked the San Francisco Bay. She also complimented the other improvements. Her appraisal value was set at $995,000. The couple was stunned and, after learning about appraisal discrimination, they decided to get another appraisal done. This time, the couple asked Joe, a white friend, to pose as the owner of the property. Once again, when the appraisal was determined, the couple was shocked. The house was now worth $1.4 million.

According to the Brookings Institution, owner-occupied homes in predominantly Black neighborhoods are often undervalued by at least $48,000 per home. This represents an estimated $156 billion in losses — hurting Black homeowners, their families, and their communities.

Other Housing Discrimination Tactics

The practices utilized by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) solidified the structured racial segregation that still exists today. When use of the color coded maps developed by the HOLC became illegal with passage of new laws in 1968 and 1974, other instruments of denial appeared as white residents and property owners created new ways to keep black home buyers from moving into their neighborhoods.

Some individual tactics may work independent of other measures whereas some often are affected by others. For example, if a home is advertised as being for sale and the best offer is made by a black buyer, the seller may want to prevent the sale by removing it from the market, a practice known as “delisting.” There are numerous published examples in which homes that were advertised as being for sale were suddenly not available when a POC showed serious interest in purchasing the property. Even rental properties were said to be already rented when the landlord found that an interested renter was black. The desire to delist may be because of an obligation through a written neighborhood “Restrictive Covenant” to not sell to a person of color. However, if the home was listed through a Multiple Listing Service or MLS, delisting may come with other legal implications. A Restrictive Covenant is a written nonstatutory agreement between a homeowner and a local entity such as a Neighborhood Association or Home Owners Association (HOA) specifying just how that property may and may not be used, developed or disposed of. It may, for example, state that a property may not be sold, rented, leased, loaned, willed, gifted or otherwise transferred under any circumstance to a person of color. Even since fair housing laws have come into being, the courts have continued to uphold such agreements based on historical housing patterns in given areas because the new laws carried no legal mandates for change and no penalties or remedies for sustaining traditional racial restrictions.

“Off market” sales are another mechanism used to transfer property only to buyers agreeable to existing residents of a neighborhood. While the term may appear to mean that the house is no longer for sale, its other meaning is that the house is still for sale but not publicly advertised. Using this tactic, a home seller spreads word of their intended sale by speaking only to friends, relatives, acquaintances and other selected associates who meet the racial, economic, social and perhaps vocational standards expected of residents of a given neighborhood. A yard sign indicating the ‘for sale’ status of a property may appear but it will not have an MLS listing. While this tactic has been used to preserve racial exclusivity, it poses some risks to the buyer since it is sometimes utilized without an agent or broker to verify such details as a clear title or the absence of property liens held by other entities. If the seller is fleeing the neighborhood due to demographic changes, this tactic may be used to pass liens or needed repair costs on to an African-American buyer without the purchaser’s knowledge until it is too late.

Even when a neighborhood or especially a new subdivision is built and populated with only white residents, people are aware that continued use of “residential security” codes will mean that their property values and borrowing capabilities may be depreciated if adjacent properties become occupied by Blacks. One tactic that often has been used to control who can own or build on a nearby parcel of land is to incorporate as a village or city in order to enact “land use regulations” limiting and/or making it necessary to obtain a municipal permit or license before building any structure. In this way existing residents can see exactly who is seeking to buy or build homes near their own and they automatically have the power to veto such plans before they are started. A developer may be allowed to proceed with home building if they commit to a Restrictive Covenant as described above. Some neighborhood groups and municipalities have attempted to further pre-empt the possibility of unintended land use by enacting “large-lot zoning” statutes to limit the type, size, use and occupancy of structures that can be erected on incorporated property.

While it may be true that the above tactics can be used to help control automobile and freight traffic, keep heavy and noisy industrial polluters away from desirable recreational and living spaces, or maintain a homogeneous architectural style, they all have been used to systematically prevent racial integration from occurring in certain residential neighborhoods. In most cases, home buyers of color are left with no option than to retreat to areas of segregated housing, thereby sustaining the very foundation of systemic racism. Therefore, while it may seem too simple to state as a solution, the most effective way to negate the effectiveness of systemic racism is to abandon its core component, racially segregated housing. It is time for black residents to use equal housing legislation to confront housing discrimination and insist on access to homes and financial services outside of the restrictive redlined limits originally designated by the government—in other words “Open Housing.”

Use of the techniques discussed above has been so pervasive and so destructive that the National Association of Realtors (NAR) actually issued a public apology in November 2020. Looking back at NAR opposition to passage of the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968, NAR President Charlie Oppler said “What Realtors® did was an outrage to our morals and our ideals. It was a betrayal of our commitment to fairness and equality. I’m here today, as the President of the National Association of Realtors®, to say that we were wrong,” Oppler said. “We can’t go back to fix the mistakes of the past, but we can look at this problem squarely in the eye. And, on behalf of our industry, we can say that what Realtors® did was shameful, and we are sorry.”

Recently appointed NAR Director of Fair Housing Policy Bryan Greene said in a related statement that “Realtors® have an admittedly tough history, but we have turned the corner and now have emerged as leaders on these important issues. Now we are talking about expanding the Fair Housing Act in ways we could not have imagined perhaps several decades ago. . . . “You can see in our neighborhoods the imprints of redlining from 80 years ago,” In an acknowledgment that denial of equal housing is a foundational aspect of systemic racism adversely affecting other extremely important economic pursuits beyond just shelter, Greene continued by saying “Many of these discriminatory practices denied the opportunities for families to pass on wealth. We see that white Americans own 10 times the wealth of African-Americans . . . So, these are serious issues, and they have broader impacts on society beyond housing. It means that we have health disparities, employment disparities, educational disparities. This is the legacy of the past… We have to address it.” The remainder of this paper will describe just how housing discrimination leads to these and numerous other negative outcomes of racial oppression.

The tactics described in Part 1 have had the intended effect of sustaining high property values for white residents while relegating black families to areas of lowered property value. Once this valuation difference is established, it is these depressed property values that are designated by municipal officials as the basis for decreased public school funding.

2: Systemic Racial Disparities in Education

For any system of institutionalized racial barriers to be effective, it is essential that those who suffer from that system remain unable to discern the structure and interconnected functions of its various components. It also is important that oppressors make sure that its victims do not gain the skills and information that would empower them to overcome, combat, avoid or escape from the system. A prime mechanism for accomplishing both goals is to sustain an inferior underdeveloped educational structure that is poorly funded and only appears to provide necessary life skills while providing little to no actual outcome value in laying a foundation for career success as an economic beneficiary.

Racial Separation in Education

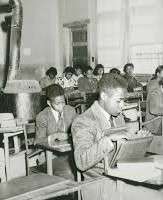

Some systemic racial educational barriers such as segregated schools are well known even though statutory segregation was officially outlawed 70 years ago. The 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown vs Board of Education of Topeka and the subsequent civil rights movement accomplished a great deal in laying the foundation for putting people of different ethnicities in the same rooms. While the results were commendable and visibly beneficial in areas such as sports, entertainment, public accommodations and the military, people have continued to be negatively affected by the attitudes instilled and information ignored in our biased education systems. While the Brown decision helped conceptualize racial separation as inherently destructive, there has been an overreliance on the power of that case to inspire change in other sectors of American society. Also, proponents of a multi-racial democracy failed to fully utilize the momentum created by the Brown decision to litigate desegregation in other cultural components such as housing, the most fundamental component of systemic racism. Racial separatists have used numerous other mechanisms to systematically relegate black children to poorly funded sparsely staffed and poorly equipped schools. Their primary tool is to utilize the neighborhood school concept in assigning each child to a specified school based on that child’s address. Under this procedure, each school is funded based on the property values assigned and taxed in a given area and each child residing within that area must attend that school. By forcing black families to only reside within predetermined residential boundaries where assessed valuations of homes are based on purposely lowered property appraisals, the children of those families are forced to attend poorly supported schools whose funding levels are determined by those intentionally depressed property values. These schools are characterized by large unmanageable numbers of pupils per teacher, small or nonexistent library facilities, old shared and poorly maintained technological facilities for both student and staff use, old and decaying recreational and athletic facilities, and sparse or woefully infrequent maintenance of the school building and its furnishings.

Some systemic racial educational barriers such as segregated schools are well known even though statutory segregation was officially outlawed 70 years ago. The 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown vs Board of Education of Topeka and the subsequent civil rights movement accomplished a great deal in laying the foundation for putting people of different ethnicities in the same rooms. While the results were commendable and visibly beneficial in areas such as sports, entertainment, public accommodations and the military, people have continued to be negatively affected by the attitudes instilled and information ignored in our biased education systems. While the Brown decision helped conceptualize racial separation as inherently destructive, there has been an overreliance on the power of that case to inspire change in other sectors of American society. Also, proponents of a multi-racial democracy failed to fully utilize the momentum created by the Brown decision to litigate desegregation in other cultural components such as housing, the most fundamental component of systemic racism. Racial separatists have used numerous other mechanisms to systematically relegate black children to poorly funded sparsely staffed and poorly equipped schools. Their primary tool is to utilize the neighborhood school concept in assigning each child to a specified school based on that child’s address. Under this procedure, each school is funded based on the property values assigned and taxed in a given area and each child residing within that area must attend that school. By forcing black families to only reside within predetermined residential boundaries where assessed valuations of homes are based on purposely lowered property appraisals, the children of those families are forced to attend poorly supported schools whose funding levels are determined by those intentionally depressed property values. These schools are characterized by large unmanageable numbers of pupils per teacher, small or nonexistent library facilities, old shared and poorly maintained technological facilities for both student and staff use, old and decaying recreational and athletic facilities, and sparse or woefully infrequent maintenance of the school building and its furnishings.

“The Black Tax”

In a March 2023 airing of MSNBC’s Chris Jansing Reports, a segment called “The Black Tax” contained a comparison of funding for schools, roads and parks in a black community and a white community. At a predominantly black Memphis school, Cummings Elementary, the building was so old and in need of repair that water was leaking from heavily stained ceilings, the gymnasium had no air conditioning and the portion of the school’s roof covering the library had collapsed sending three adults to the hospital emergency room. A staff member stated that the bathroom fixtures, drinking fountains, lockers and other items of equipment were the exact same objects that were in place years earlier when she attended that school. It was learned that Memphis schools in majority black areas had been attempting to function while accruing one-half billion dollars in deferred maintenance costs.

The very existence of poor majority black areas of Memphis is a direct result of the redlining practices exposed by the Justice Department in the lawsuit cited above against Trustmark National Bank. As a result, Memphis simply could not afford the substantially higher borrowing rates charged to communities in which a majority of the residents are black. Consequently, about a third of Memphis schools are more than one hundred years old. It was reported that while the majority black community can exhibit a fiscal record equal to white communities in managing municipal finances, those who administer the bond market still charge black municipalities much higher interest rates on municipal bonds, thereby making it difficult and often totally out of reach for a town or city’s budget. In that same segment, Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris reported that he is demanding answers from bond lenders who set those higher rates even though Memphis has demonstrated their ability to effectively manage their debt load. By comparison, the all-white town of Collierville, also in Shelby County just 20 minutes from Memphis, was reported to have a higher bond rating giving them lower interest rates which had allowed them to recently open a new 100 million dollar high school.

Even towns with a low percentage of Black residents suffer from the ‘black tax’ as these areas are unfairly penalized for nothing else but their demographics. Studies show that even after controlling for all other variables, municipalities that were more racially diverse were offered municipal bonds with higher bond insurance rates and a lower credit rating, which led to higher interest rates and put the cities in a worse financial position. Destin Jenkins, a historian of capitalism at Stanford University, has written that segregated white suburbs benefited from high credit ratings which entrenched municipal wealth during the period after World War II. Conversely, he argues, investors punished Black towns for their shoddy infrastructure and lack of access to capital. When bond rating agencies like Moody’s assessed the creditworthiness of cities, they would penalize Black towns for racial inequality that persisted from slavery. Jenkins wrote that “Bond rating analysts participated” in the process of racial segregation. This puts the bond rating system in partnership with home appraisers as the twin pillars forming the very foundation of systemic racism: With the inability to obtain federally ensured bank mortgages, lack of opportunity to profit from home sales due to artificially low home appraisal values, and the inability to raise capital through municipal bonds, residents of diverse communities are forced to delay housing investments and postpone or omit improvements in schools, streets, sewers and parks. The only alternative is to raise local taxes to sustain essential municipal services amid constantly rising costs which further depletes what household income the residents might have had to live on. Note also the domino effect in that studies and experience show that without good schools, roads and parks, it is nearly impossible to attract new industry to provide jobs that might improve household incomes.

David Dubrow, an attorney with Arent Fox Schiff and an expert on municipal finance, says this racial inequality in the bond market can trap Black cities in a cycle of disinvestment. “What we’re talking about is a reinforcing cycle of penalizing poor communities that are already poor,” he told Grist. “The impact on the community is higher taxes and less money for social services” or for repairing or replacing school buildings. The difference of a few percentage points in the interest rate of a bond can add up over the course of decades, placing a huge financial burden on cities. In a recent article, Dubrow’s firm estimated that because Milwaukee, where over 40 percent of the residents are black and which has a lower credit rating than other cities of its size, the city will pay an extra $477 million to borrow money on a 30-year bond. Dubrow’s firm also suggested that Congress could offer more direct grants for infrastructure improvements, or that the U.S. Treasury could ensure local bonds, which might alleviate investor fears of default. Sondra Collins, a senior economist at the University Research Center for the State of Mississippi, said that given the persistence of racial discrimination in the municipal bond market, the best thing to achieve equity is to rethink the system as a whole.

Some researchers believe that personal implicit bias among people working to issue and rate bonds could play a role in disparities between the types of municipal bonds offered to white and black cities and towns. “They’re unaware that they hold that bias,” said Municipal Credit Analyst Dr. Erika Smull, “And they just associate a city that is predominantly Black with images that have been curated in their mind over time.” Most of these images, said Smull, are the types of negative stereotypes that have persisted in the American imagination. This includes the idea that it might be a risk to invest in a town with a higher percentage of black residents, despite the fact that the credit risk might be the same for a white and black town but their rating could be set lower. Note that a 2016 paper entitled “Prevent Lethal Implicit Bias: Stop Media Implanted Bias” successfully demonstrated that racial bias is not “implicit.” Rather it is Implanted through repeated media conditioning associating Black and Brown ethnicity with crime, violence and failure in school or vocational pursuits. Within three years after publication, most news outlets stopped traditional biased race reporting practices that had been in place for centuries and many published apologies to their black constituents. The damage, however, may take generations to undo since biased racial images remain in the minds of those in the ‘justice’ system, in housing, in business and finance, and throughout our educational systems—especially in classrooms.

School Discipline as a Tool of Systemic Racism

In addition to a tradition of systematic bias in selection of information to be taught in classrooms, there is objective data showing that elementary and high schools are places of systemic discrimination in their methods of disciplining students. According to the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights, black students are three times more likely than white students to be suspended or expelled. A research report by the Justice Policy Institute found that in Texas, suspended students are more likely to be held back a grade and drop out of school. For those who do manage to stay in school and succeed in moving forward, the economic disadvantages for people of color continue long after they have graduated from college. Twelve years after entering college, white men have paid off 44% of their student-loan balance on average, according to an analysis released last year by Demos, a left-leaning think tank. However, black men see their balances grow 11% and black women by 13%.

Many school officials have fallen victim to traditional thinking believing that stricter discipline and tougher punishments with armed ‘resource officers’ will force students to behave while in school so that teachers will have an easier time getting everyone through the day. However, both experience and research show that compliance and motivation to learn are not enhanced by the threat and use of violence. Undisciplined pupils need guidance from counselors more than they need cops. Students need to know that there are both firm limits on the range of allowable behaviors at school and strong consequences for violating those limits. A third closely related absolute necessity must be their awareness that exciting opportunities are available to be pursued while functioning within those limits. It is counterproductive to subject them to expulsion as it forces them to spend unsupervised time outside of school where many are left to be raised by street predators and police officers, especially when parental supervision is not available due to work responsibilities, judicial restrictions or other factors. Society will be much better served by working with children in school to help them build self esteem, set goals and be mentored, motivated and educated instead of the much more costly path of filling more and more prisons with intelligent individuals who then learn how to become more and more dangerous as their chances for legitimate acceptance and success decrease with every moment spent under judicial supervision.

Overcoming Bias in Classroom Teaching

Schools, colleges and universities have invested years of effort into diversity programs that offer students the chance to see people of color as colleagues and in positions of authority and leadership. Many also offer special training designed to help targeted students remain productive despite episodes of racism. However, they have avoided efforts to confront or dismantle sources of racism itself. These efforts are noble but do little to change or rebuild an ingrown mindset of racial victimization among POC or racial favoritism among whites. In order to achieve effective systemic change, it is the CURRICULUM that is most in need of diversification. The information that people learn will have a greater and more lasting impact on their future behavior than who assigned them to learn it or who else was in the room and got the same assignment. I know this first hand because in elementary school, all of my teachers, principals and all classmates were black, but other than slavery, no subject matter featured black individuals, ideas, inventions, or accomplishments. Today’s pupils learn about some civil rights leaders, but many schools have given in to historical revisionists who prefer to omit mention of slavery as a reality in our nation’s history. When black pupils internalize the resulting implication that there is nothing of importance that blacks do or have done to succeed, it can impair their ability to value themselves, respect others or become motivated to achieve or even to participate in pursuing a future that may bring them educational, vocational or economic success.